Better Climate Models predict worse outcomes for future marine ecosystems in warming oceans (Scripps)

par Lauren Fimbers Wood sur le site de la Scripps

A new study in Nature Climate Change by a science team including researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego used next-generation climate models to provide insights into how projected climate change will affect future ocean ecosystems.

They found higher climate risks for marine ecosystems, and that reducing uncertainty in how marine ecosystems respond to climate change will support more effective adaptation planning.

Climate change caused by humans is a growing threat to marine ecosystems, with impacts projected to intensify responses in marine animals, including increased mortality, reduced calcification caused by ocean acidification, and changing species distributions, interactions, abundance, and biomass. Combined with stressors like overfishing, the societal benefits that come from the ocean are also under threat.

An interdisciplinary team of 36 researchers working across 29 research institutions and based in seven countries contributed to this important study as part of the Fisheries and Marine Ecosystem Model Intercomparison Project (Fish-MIP).

Colleen Petrik is a biological oceanographer at Scripps Oceanography who specializes in understanding how the physical marine environment affects the ecology of zooplankton and commercially important fish. For the study, she interpreted the climate change impacts on ocean physics and plankton as simulated by two Earth system models that generated projections of the marine environment to 2100. She also contributed to projections of future marine animal biomass using a marine ecosystem model she co-developed.

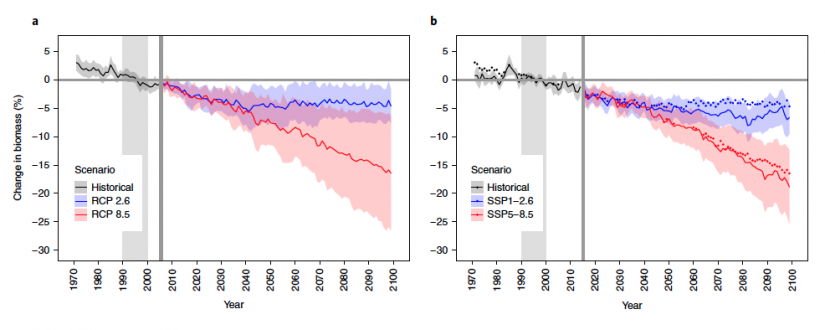

"Using the next generation of climate models with the next generation of fisheries and marine ecosystem models not only shows a larger decline in marine animal biomass than the last generation, but a clear separation between strong mitigation and high emissions greenhouse gas scenarios,” said Petrik. “In the old estimates, there was some chance that both emissions scenarios would result in the same change in marine animal biomass, but these new results demonstrate that continued high emissions is much worse for marine life."

Study co-author Camilla Novaglio, from the University of Tasmania Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies and the Centre for Marine Socioecology, said it is vital to understand the risks of climate change for marine ecosystems – and the benefit of mitigation.

“Projections of climate change impacts on marine ecosystems reveal long-term declines in global marine animal biomass, and show that the impacts on fisheries are unevenly distributed,” said Novaglio. “Our simulations show that elevated warming, and changes in the availability of nutrients and food, will create a more marked decline in animal biomass in the world’s oceans than previously assessed.”

The study also found that the declines in marine biomass shows a greater separation between high-emissions scenarios compared to those with strong mitigation efforts, emphasizing the benefits of working to reduce emissions. The increased warming that results under high-emissions scenarios comes at a metabolic cost to marine organisms, increased ocean stratification, and a decrease of phytoplankton and zooplankton.

“While our results show worrying trends, we also highlight the importance of better understanding regional changes, where there remains considerable uncertainty yet there is an urgent need to help support adaptation,” said lead author, Associate Professor Derek Tittensor of Dalhousie University saidys,.

This study brought together disparate marine ecosystem models to allow scientists to better understand and predict the long-term impacts of climate change on fisheries and marine ecosystems, and provide an evidence base that will help to inform fisheries, climate change, and biodiversity policy.

The study represents a stepping stone in planning future pathways towards sustainability, and is a major contribution to the sixth Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Assessment Report (IPCC AR6), due for release next year.

The study authors also hope this study will be utilized by world leaders and policy makers at events such as the UN Climate Change Conference (COP 26) in discussion and planning of commitments to combat climate change.

The study was funded by a variety of international sources. NOAA supported Petrik’s research.

Adapted from University of Tasmania.